AUTUMN 2016 ISSUE

LIVESTOCK MATTERS

14

HERD HEALTH

James explains: ‘It takes around one hour to

make an evaluation of a bull’s breeding

soundness, depending on its temperament

and the handling facilities! But once the vet

has set up the tools required, like the

microscope with heated stage for evaluation

of sperm motility, then any further bulls can

be tested in around 20 minutes.

‘Good handling facilities and a crush which

gives the ability to examine the underside of

the bull, help speed the procedure.‘

The BBSE covers the full range of parameters

that impact on fertility and fitness.

It includes assessments of libido, body

condition score (optimum range is 3.0-3.5

in a working bull) and checking for lameness.

‘This is a common issue: bulls are heavy,

especially the Continental beef breeds, and their

feet are under a lot of pressure,‘ says James.

Young bulls can also be prone to ‘ascending

infections’ from riding other animals: bacterial

infection spreads up the reproductive tract

and into, for example, the testes, where it

can lead to pus or blood in the vas deferens

which kills the sperm. Similarly, the accessory

glands (which provide fluids that make up the

ejaculate) can become infected.

‘Size does matter! A scrotal circumference of

34cm is the minimum standard. But young

bulls can sometimes not have the size to

produce high quality sperm,‘ explains James.

Sperm is assessed for percentage of live versus

dead sperm, motility and any morphological

abnormalities. James explains: ‘Any infections

or diseases that increase temperature are

detrimental to sperm quality. It can take a

month for normal spermatogenesis to resume.

Also, stress increases levels of cortisol in the

blood and this has the same effect.

‘Some bulls suffer erectile dysfunction, and

spiral deviation is another physical feature

which prevents sperm from being deposited

in the right place.

‘Physical injury to a bull’s penis is also

always a possibility.‘ And that was the case

with one of Sam Barker’s Longhorn bulls…..

Keep your eye on the bull!

Sam Barker and his wife Claire, and parents

Steve and Julie, run a 110-cow herd of

Longhorn cattle on an organic all-grass system

with no bought-in feeds. Boxed beef and

pies are sold via the farm shop, farmer

markets, and the internet.

Sam explains: ‘When we switched from

organic dairying to beef production in 2004,

our aim was to produce quality meat rather

than looking for quantity. So we selected

the Longhorn breed, and continued on our

organic system.

‘When we first started, we needed to finish

animals all year round. So we ran the bull

with the cows for a 6-month period, and

had a very extended spring calving block.‘

But following advice from his vet James

Marsden, Sam accepted that he could have

a short calving block and then alter the

forage ration to adjust subsequent growth

rates to get a spread of finishing times. Once

cattle reach 24 months of age, they are

allowed to finish ‘at their own pace’, and are

slaughtered around the 28-30 month mark.

By 2008, Sam had converted the herd into

a single short block of spring calving.

But then in summer 2012, one of Sam’s bulls

damaged its penis partway (3 weeks) into

the breeding period. This was only discovered

when James visited to PD the cows. It took

several weeks to find a replacement bull,

and ultimately led to a 2-month gap with no

calvings the following spring.

From this situation, a small autumn calving

herd was created, and the herd was run with

two calving blocks.

However, Sam has discovered there are

benefits in autumn calving. ‘The farm is

capable of producing good quality forage,

and the sandy soil means minimal damage

to the pasture over the winter. I’m weaning

the autumn-born calves at 10 months instead

of seven, to stop their dams getting too fat.

The calves are outwintered with their mothers,

thereby avoiding pneumonia risk and the

extra work of being housed. I’m not seeing

any growth check at weaning, and they

grow faster overall,‘ says Sam.

‘By comparison, the spring-born calves are

weaned late November. This stresses them

and additionally there is the stress of being

housed. So there’s a greater risk of

pneumonia.

‘So this year, I shall sell or slaughter the

heifers from the spring calving group. And

instead, I’ll only rear replacements from the

autumn calvers. The aim is to calve these

down at 2 years of age, and gradually

transition to a single calving block – in the

autumn.‘

James adds: ‘This year, we PD-ed the spring-

calving group 70 days after the bull had

gone in and found that 75% were over 30

days in-calf. So we're on track to achieve a

compact calving block.

‘We are also aiming to be weaning a calf

from at least 95% of heifers and cows, and

finishing them at 26-30 months of age.‘

James explains: ‘So as well as giving all

bulls a pre-breeding examination, it’s also

important to keep an eye on them throughout

the breeding period, and watch that they

remain physically fit and active.

‘Sam was lucky. Having an unfit bull turned

into a ‘happy accident’ as he discovered that

calving in autumn is the best option for his

herd.‘

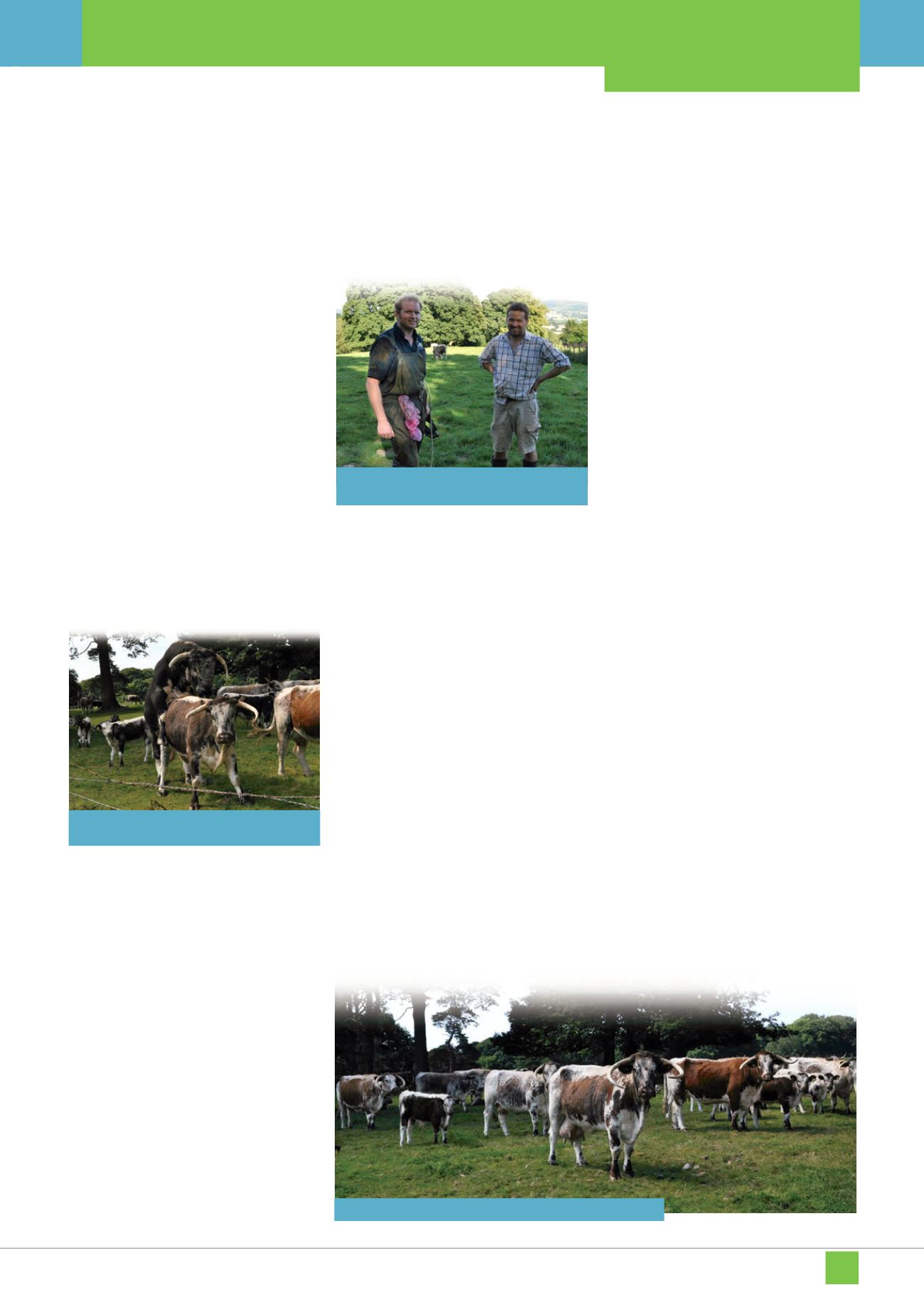

Longhorns, despite their long horns, are a very placid breed

Pregnancy diagnosis of the spring calvers shows the

herd is on-track to calve down in a compact block

Lameness is a common problem, particularly in

continental breeds