SPRING 2016 ISSUE

EQUINE MATTERS

6

Nuclear scintigraphy

Nuclear scintigraphy or bone scanning is most

commonly used in the investigation of under

performing horses where the cause of the

problem is not clear and a general approach

is required, or when multiple limbs are

affected. Often horses are not obviously lame,

rather just lacking propulsion or disuniting at

canter. A radioactive phosphate molecule is

injected into the horse’s bloodstream which

binds to the bones of the skeleton. Any areas

of the skeleton which are damaged will bind

more of the molecule than normal and will be

visible when images are taken with a gamma

camera. The entire skeleton can be examined

in a single session (taking about two hours)

with the horse under standing sedation. Bone

scanning is particularly important for diagnosis

of back and pelvis injuries

(figures 1 and 2)

,

but is also useful for head, neck and leg

issues. Once the problem area is identified,

further imaging such as radiography will likely

be required to characterise the exact nature of

the injury.

Magnetic resonance imaging

MRI gives an extremely detailed three

dimensional view of all types of tissues, but

can only examine small areas at a time. Most

machines are currently only large enough to

allow imaging from the top of the cannon

downwards, and examination is limited to

a single area at a time, e.g. the fetlock

(figure 3)

. The area to be examined is placed

inside a powerful magnet and radio waves

are applied. The signal produced varies

according to different tissue characteristics,

allowing a computer to create an image of

the horse’s leg in which all the different tissues

can be clearly identified and analysed for any

abnormalities. MRI is indicated when the

location of a cause of lameness has to be

regionalised, usually with nerve blocks, but

conventional imaging modalities have not

identified the problem. It is most commonly

used to examine horses’ front feet

(figure 4)

and has significantly improved our

understanding and management of foot pain.

Computed Tomography

CT is essentially a three dimensional

radiograph. The area to be examined is

placed inside a helical x-ray generator and

images are taken in a circular fashion.

Using a computer, a 3D image can then

be developed which provides detailed

information of the position and density

of adjacent tissues and avoids the

superimposition of tissues which plagues

standard 2D radiographs. CT is most

commonly performed in standing horses

to examine the head for dental or sinus

disease, or the neck for causes of

incoordination (Wobbler's Syndrome).

CT is also used in anaesthetised patients to

examine the legs, allowing appreciation of

complex fractures prior to reconstructive

surgery, or in combination with a contrast

agent to look at soft tissue disease. In some

cases it is now possible to get a horse’s

stifle into a CT machine to investigate the

joint cartilages and cruciate ligaments.

As in human medicine, diagnostic imaging

for equine patients is advancing rapidly.

Machines are becoming larger and more

powerful every year, allowing more areas

of the horse to be examined and more

detailed images to be produced. Perhaps

the days of a ‘whole horse scan’ are not

that far away.

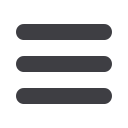

Figure 1. Bone scan of the back. Nuclear scintigraphy image of the

left side of a horse’s back. A clear ‘hot spot’ is seen at the centre of

the back, directly under the weight of the rider. This is indicative of

‘kissing spines’ (blue arrow).

ADVANCED IMAGING

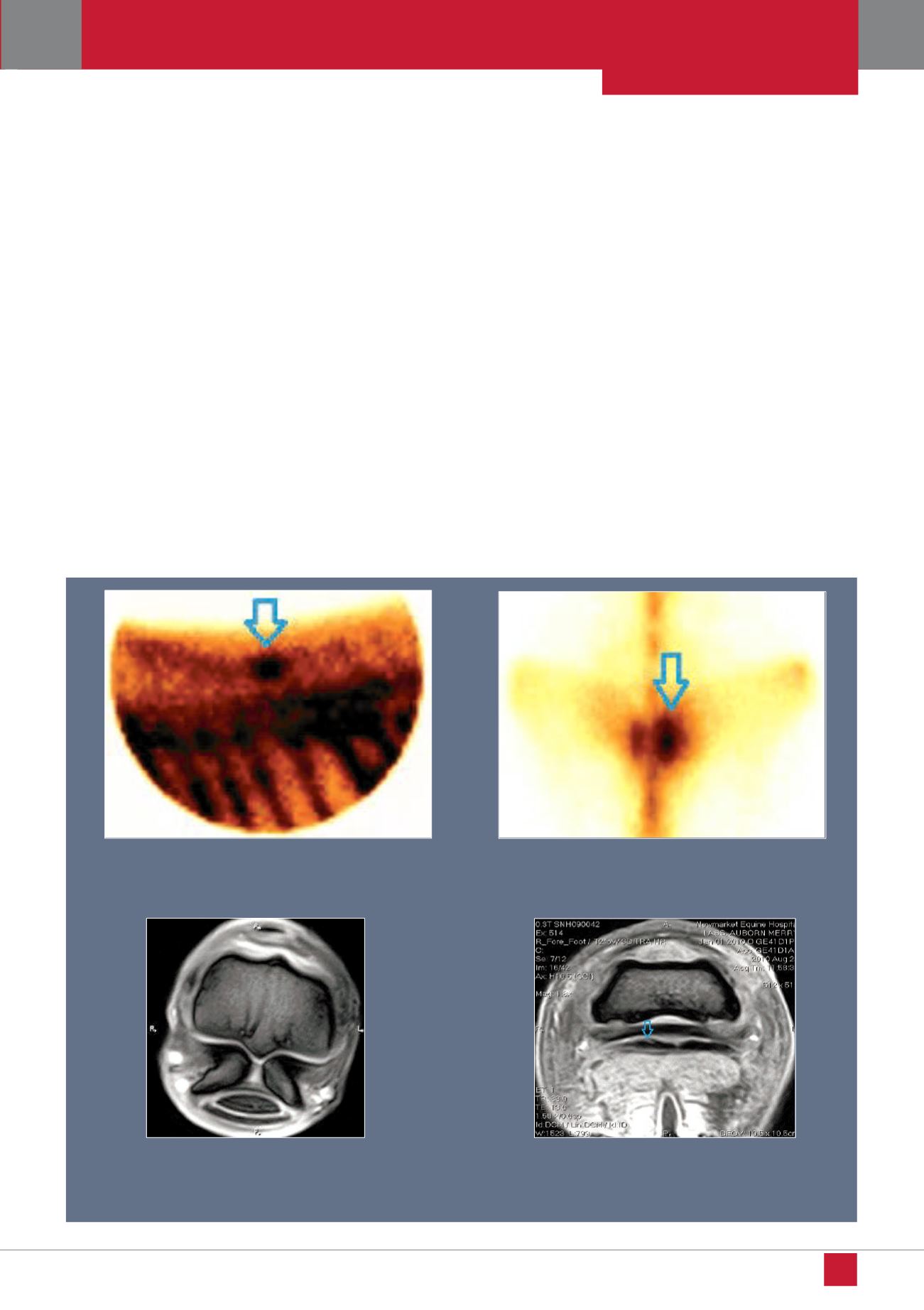

Figure 3. MRI fetlock.

MRI image of a normal horse’s fetlock joint

taken parallel to ground level. Excellent detail of bone density,

cartilage thickness and tendon integrity can all be seen on the same

image.

Figure 2. Bone scan of the pelvis.

Nuclear scintigraphy image of

a horse’s pelvis from above. There is much more uptake of the

radioactive ‘dye’ in the right sacroiliac region when compared

with the left (blue arrow), indicating right sided sacroiliac disease.

Figure 4. MRI Foot.

MRI image of a horse’s foot taken parallel to

ground level. A tear can be seen in the deep digital flexor tendon

(see blue arrow above). This injury is not visible on radiographs

and due to the structure of the hoof, cannot be easily identified by

ultrasound examination.