SPRING 2016 ISSUE

EQUINE MATTERS

14

D I ARRHOEA

Acute watery diarrhoea in a foal or adult

horse should not be ignored and warrants

discussion with your vet. One of the main

functions of the horse’s colon is to reabsorb

water, therefore profound diarrhoea usually

suggests significant disease of the colon.

This is often called ‘colitis’, especially if

inflammation of the colon wall has occurred.

Dehydration can rapidly occur due to the

ensuing massive water and electrolyte losses,

possibly leading to endotoxaemia or ‘septic

shock’

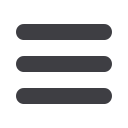

(figure 3)

. Horses can lose up to

50-100 litres of fluid in 24 hours due to

diarrhoea and so can deteriorate very quickly.

Following initial digestion in the stomach and

small intestine, food material passes into the

colon and caecum - a huge voluminous

reserve containing millions of ‘friendly’

bacteria. It is here where fermentation and

digestion of plant material occurs in the horse

that otherwise would be indigestible and a

wasted food source. It is also at this location

that fluid is secreted and absorbed to

maintain intestinal water regulation of the

horse. Therefore, when there is damage to

the colon wall and it can no longer regulate

this balance, diarrhoea occurs.

There are multiple causes of diarrhoea in

the adult horse and often, despite repeated

clinical examinations and extensive

diagnostics, a definitive diagnosis can be

frustratingly difficult to identify. However,

treatment is often similar and therefore can

be initiated before a specific diagnosis is

made. Causes of diarrhoea in the adult horse

include infective agents, such as

Salmonella

spp. or Clostridial bacteria and parasitic

infections, most commonly small strongyles

(redworm/cyathostomins). Non-infectious

causes include recent antibiotics or

non-steroidal anti-inflammatory administration,

toxin or sand ingestion. Sometimes anxiety

alone in a nervous or fractious animal will

lead to the temporary production of

watery faeces.

Diagnostic investigations include assessing

faecal material for larval stages of small

strongyles (redworm), bacterial culture and

DNA analysis of faecal samples.

Ultrasonography of the intestinal wall can be

very useful for assessing and measuring colon

wall inflammation and thickening, and may

help specify a diagnosis. For example, in

cases of diarrhoea related to recent

nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID)

administration (e.g. ‘bute), a specific

syndrome of colitis of the right upper colon

occurs (known as right dorsal colitis), which

can be identified ultrasonographically. Bloods

are often taken to assess the degree of

inflammation present, to help rule in or out

infectious disease, and to assess the degree

of dehydration.

If a causal agent is identified, treatment

can be tailored more specifically, however

general treatment principles include

correction of dehydration and restoration

of normal electrolyte balance. This can be

achieved through oral fluid supplementation

or, if required, via an intravenous drip.

The inflammation may be severe enough for

protein to be lost across the intestinal wall

resulting in low protein levels within the

blood. Clinically this may be apparent as

oedema or fluid swelling of the lower legs

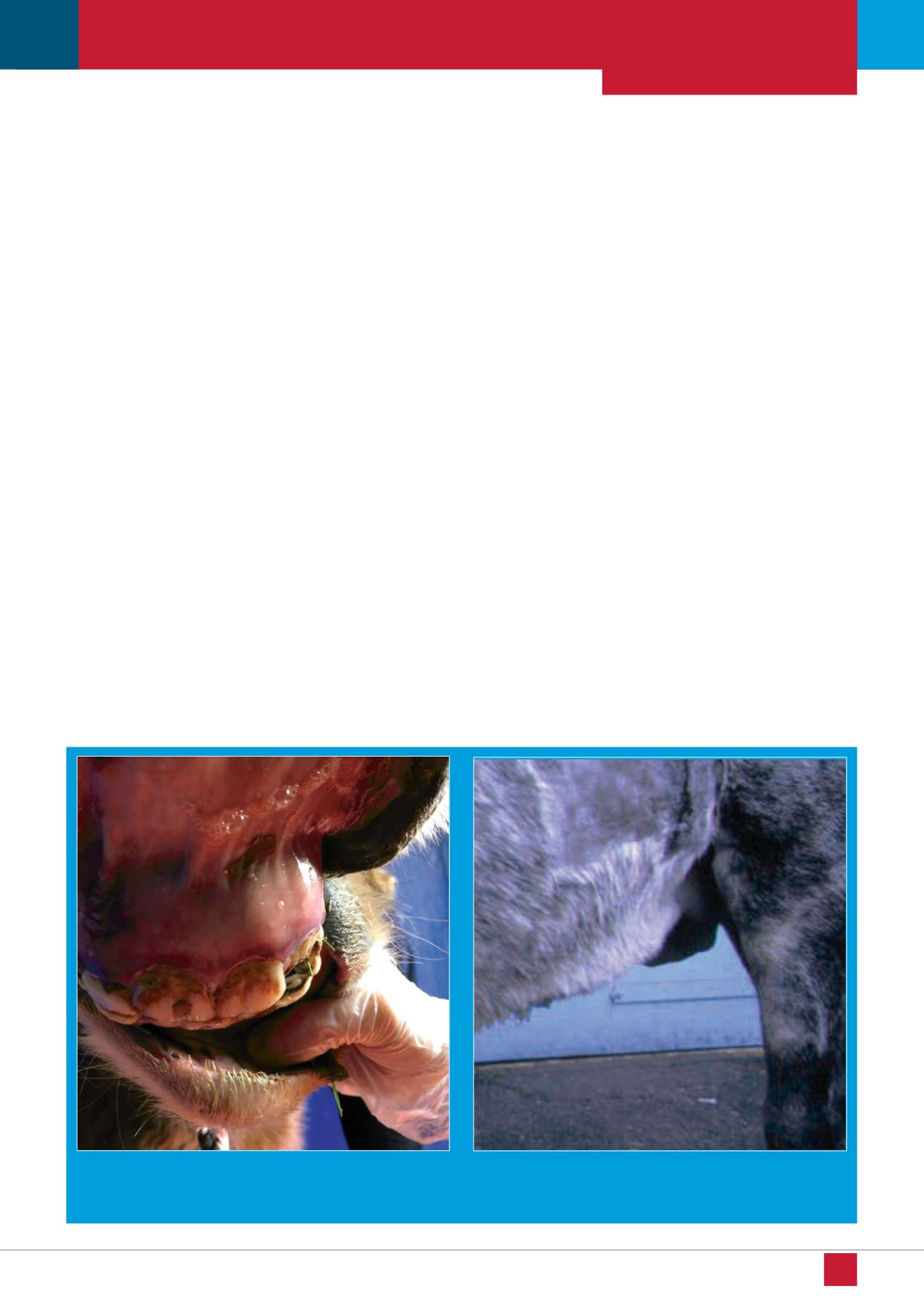

and under the belly

(figure 4)

. In very

severe cases, intravenous plasma may be

needed to restore blood protein levels.

Use of antibiotics in diarrhoea is controversial

and generally not advised as their use can

directly result in diarrhoea. Anti-inflammatories

will often be administered for both treating

the pain associated with acute diarrhoea

and also for controlling the inflammation;

however, they must be used carefully, as they

can further compromise the bowel health and

lead to other further complications in a

dehydrated patient.

For mild cases which remain bright and

eating without systemic signs, a course of

probiotics alone may be utilised to help

restore hindgut bacterial health, although

there is little scientific evidence to support

their use. Other additional treatments may

include bio-sponge, an oral product which

can help support a healthy intestinal function

and can absorb toxins from the bowel.

The prognosis for a mild case of diarrhoea is

generally good, although more severe cases

of colitis carry a far more guarded prognosis.

Figure 3.

Gums that are deep red with a purple ring are a hallmark

feature of septic shock

Figure 4.

Oedema (tissue fluid) accumulation under the belly in a

horse with low blood protein due to redworm (small strongyle)

associated diarrhoea