5

EQUINE MATTERS

ANTIMICROBIAL

RESISTANCE

Veterinary surgeon

Dr Imogen Burrows

XLEquine practice

Cliffe Veterinary

Group

A complicated castration

Dr Imogen Burrows BVetMed CertAVP(EM) MRCVS,

RCVS Advanced Veterinary Practitioner in Equine Medicine

Cliffe Equine Clinic

Castration is one of the commonest surgical procedures performed in

veterinary practice and is generally straightforward, however as with

any surgical technique complications can and occasionally do occur.

Figure 1. Bracken as a foal

Bracken, an 18 month old cob, was a very

friendly, amenable chap, having been raised

in a rescue centre from an early age

(figure

1)

. Once rehomed, his owner’s vet made

the decision to perform a standing open

castration. The procedure went smoothly

and initially the healing process proceeded

normally.

Unfortunately, a couple of weeks down the

line it became clear things were not quite

right. The owner noticed that Bracken

appeared to be walking with a slight waddle.

On closer inspection, she noticed that his

scrotum was very swollen with discharge

coming from the castration wound.

The owner rang her vet to seek further

advice. After examination, it was clear that

the castration site had become infected.

Under sedation, the incision was reopened

to ensure infected fluid was not being

retained and to allow drainage. Bracken

started on a course of broad spectrum oral

antimicrobials to try and combat infection,

along with anti-inflammatories to ease his

discomfort and reduce the swelling.

Unfortunately, Bracken’s luck was not

improving. Ten days later there was no

significant improvement in the discharge or

swelling, although Bracken behaved

completely normally otherwise. The vet

recommended further investigation and

performed an ultrasound examination of the

swollen area. This confirmed that the ends

of the spermatic cord were very thickened,

along with a lot of swelling of the surrounding

soft tissues, but no abscess had formed.

The vet recommended the best treatment for

this type of infection, known as a scirrhous

cord, was to remove the infected tissue

surgically. Correction of a scirrhous cord requires

the horse to be anaesthetised, as the horse

must be lying on his back to allow access to

the infected area. Understandably, the owner

was very worried about a second, more

invasive surgery and discussed other possible

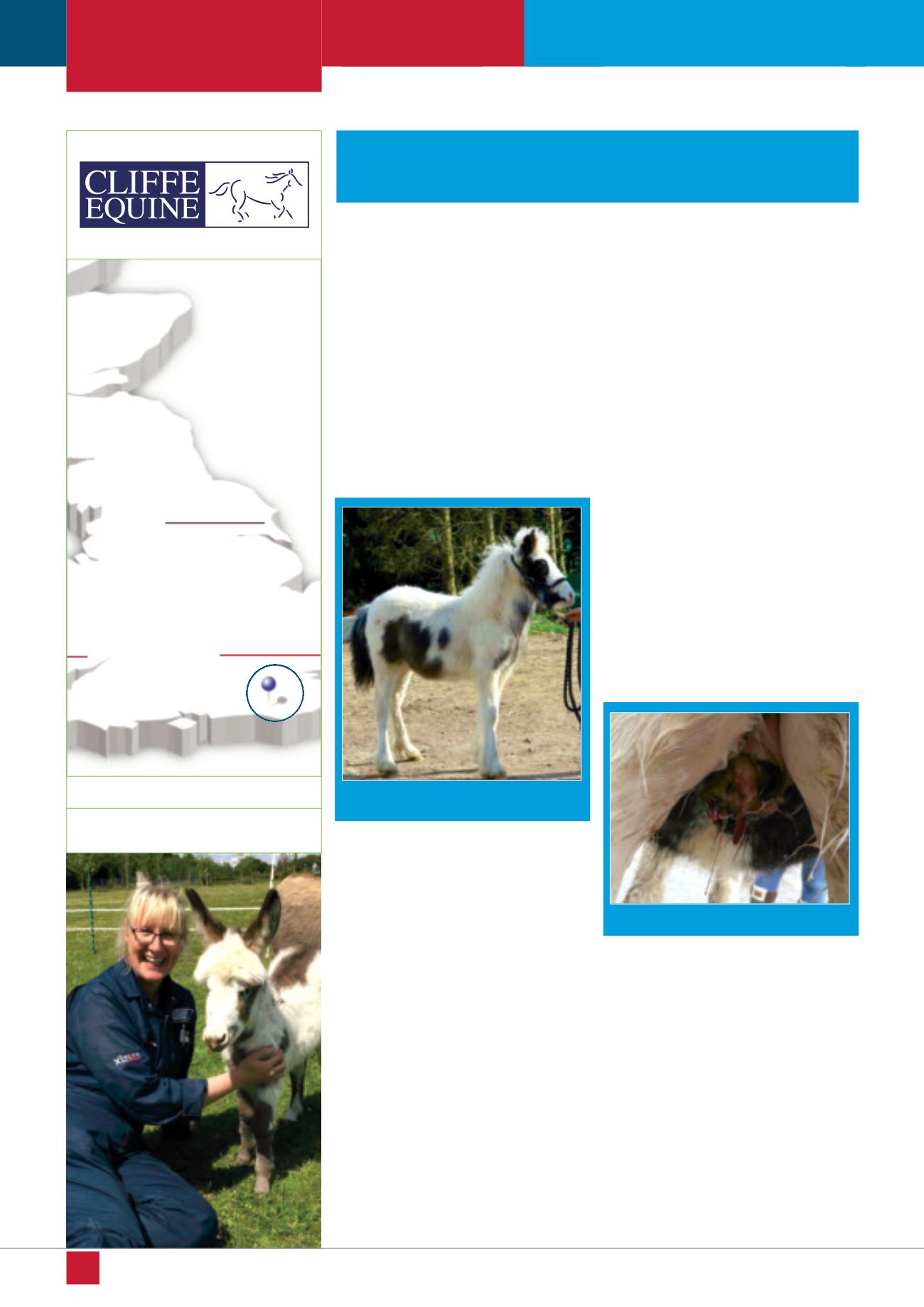

medical options with her vet. Bracken was

given another course of oral antimicrobials,

but the infection persisted and over the next

two weeks became worse

(figure 2)

.

Feeling worried, the owner contacted the

yard from which she had rehomed Bracken

for help. The yard manager agreed to help,

and offered to care for Bracken at the rescue

centre until the problem had been resolved.

At this stage Bracken was examined by the

vets for the rescue centre, Cliffe Equine.

Working closely with the original veterinary

surgeons, all parties agreed that Bracken

needed surgery.

At surgery it was clear that about six inches

of cord was thickened and infected, but the

junction with normal cord deeper inside could

be clearly seen

(figure 3)

. Exposing and

removing a section of the normal cord was

very important to prevent recurrence of the

Figure 2. The infected castration site