Basic HTML Version

LUNGWORM PREVENTION

WORKING

TOGETHER

FOR A HEALTHIER FUTURE...

17

LIVESTOCK MATTERS

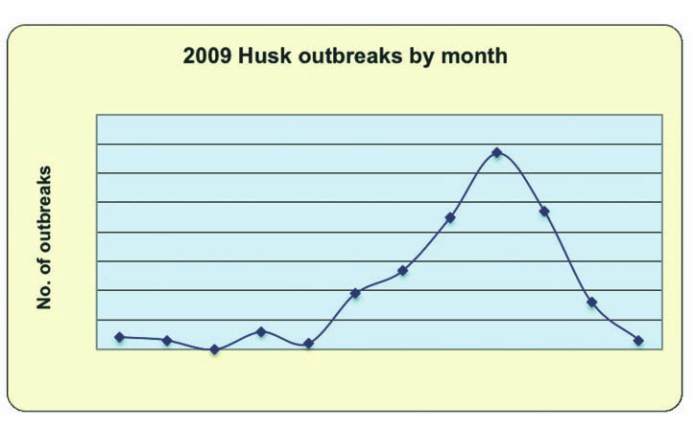

Traditionally, the time to start considering husk (lungworm) prevention is just before turnout. Given that

lungworm still remains a constant threat year on year, and turnout will be starting in some parts of the

country soon, planning how best to protect stock from the continued threat of lungworm will pay

dividends as the season progresses. Although outbreaks are seen mainly in late Summer and Autumn

(see graph below), early planning is the key to prevention.

Time to protect valuable

stock from

Lungworm...

Historically, lungworm problems have

been most commonly associated with

youngstock, but now almost 75% of

reported cases are in adult animals,

which could have a very significant

impact on the profitability of a herd.

Iain Richards from the Westmorland

Veterinary Group based in Kendal believes

the re-emergence of husk as a disease in

recent years is largely down to a reduction

in vaccination and changes in modern

worming practices.

‘When I first qualified 20 years ago you

just didn't see husk problems in cattle,

largely because vaccination was much more

prevalent. But around 10 years ago we

started to see it appearing again and it

can only be because current lungworm

control regimes are not working well enough.

If all you are going to use to worm your

cattle is a long-acting wormer with no

immunity development opportunities, it

could easily compromise your lungworm

control,’ he warns.

Westmorland Veterinary Group takes an

active interest in parasitology within the

practice. ‘We need to start taking a similar

approach with cattle as we do with sheep

under the SCOPS regime, and try not to

worm unless you have to. Recently, we've got

quite adept at finding evidence of lungworm

infections in cattle. The test is a little fiddly,

but quite straightforward, and we can have

a result overnight. And showing evidence

of the presence of lungworms does help to

convince farmers to implement a vaccination

regime,’ Iain says.

Iain maintains that planning lungworm control

strategies prior to a heifer's first grazing

season makes sense and doing so can

avoid the all-too-common scenario where an

infestation does occur later in the season

and treatment has to be given.

‘As well as being costly, lung damage will

often have already occurred, leading to the

typical signs we see in infected animals. In

youngstock the main effect is a depression in

growth rates, leading to a longer finishing

period or time to first service. In older cattle

the disease can depress milk yields and

depress fertility.’

Husk occurs as a result of infection with the

lungworm Dictyocaulus viviparus. Cattle

develop it after eating grass contaminated

with infective larvae. Once in the gut, the

larvae migrate through its wall and a few

weeks later reach the lungs where they begin

laying eggs. A spell of mild, wet weather can

create a sudden, dramatic increase in

lungworm populations, which can be very

harmful, even fatal, to any stock that have

little or no immunity.

‘Even where prevention is the goal, relying on

wormers alone doesn't allow the animal to

develop its own natural immunity,’ Iain Richards

says. ‘Ideally, at the start of the season you

should sit down with your vet and plan your

herd worming strategy, but controlling husk

should be the number one priority. Vaccination

with a pre-turnout course of Bovilis Huskvac

®

is the most reliable way of ensuring the

development of immunity to lungworm. When

you consider how much is invested in cattle

genetics, and the value of 24-30 month old

heifers, in particular, it makes no sense at all

not to vaccinate against lungworm when the

vaccine is such an effective product.’

Bovilis Huskvac is a live vaccine, made

from irradiated larvae, which are incapable

of causing disease. For dairy calves,

vaccination should be completed at least

two weeks before the calves are turned

out to grass, for suckled calves it should

finish two weeks before the calves begin

to eat significant amounts of grass.

Sustained-release wormers such as boluses

should not be given until two weeks after the

final dose of vaccine.

The vaccine produces a very good immune

response against disease but it does not

prevent all worms from natural infections

completing their life cycle. This allows for the

continued development of natural immunity,

which often fails to occur where there is an

over-reliance on wormers.

Jan

Feb

Mar

Apr

May

Jun

Jul

Aug

Sep

Oct

Nov

Dec

Coughing cow