Basic HTML Version

L AM E N E S S

SPRING 2012 ISSUE

EQUINE MATTERS

4

Figure 3

The horse is walked and trotted on

a firm surface

3. Gait analysis

The next part of the lameness examination

will evaluate the horse's gait. The horse will

be observed at walk and trot in-hand (see

Figure 3). The vet may require your horse to

be walked or trotted in-hand, lunged (Figure

4), or ridden on soft and hard ground.

Usually at this stage of the examination it

will become apparent if the horse is lame

and if so, which leg/legs are affected.

Figure 4

Lunging is often used in the

assessment of lameness

4. Flexion testing

Flexion tests may be helpful if the lameness

is subtle or there are no obvious signs of a

problem. Typically, flexion tests involve

bending or "flexing" a joint for 30 seconds

to two minutes. Then the horse is trotted for

about 20-30 metres and evaluated for an

increase in lameness. If a particular flexion

test intensifies the lameness, your vet may

concentrate on that area of the body or

that joint as the source of the lameness

during the rest of the examination.

When performing diagnostic nerve blocks

(shown in Figure 5), local anaesthetic is

infused either around a nerve or injected

into a joint or other synovial structure,

e.g. tendon sheath, bursa, etc. If the

lameness disappears or improves markedly

following administration of anaesthesia,

your vet will have successfully localised

the site of lameness.

After nerve blocks have localised an area

causing the lameness, diagnostic imaging,

e.g. radiography, ultrasonography, etc,

can be used to further understand the

lameness condition. If the lameness

cannot be localised by nerve blocks,

other diagnostic imaging techniques can

be employed. Occasionally, the process of

‘blocking’ will be by-passed and diagnostic

imaging will be performed, particularly if

the affected region is already identified.

Figure 5

A nerve block being performed

5. Diagnostic local anaesthesia

(nerve or joint blocks)

6. Diagnostic imaging

Radiographs (x-rays) are used to show

changes in bone and joint surfaces once

the area causing the lameness has been

identified. X-rays can be extremely useful

in the investigation of lameness but require

careful interpretation however, as x-rays

may reveal historical changes in the

bone which are not related to the current

lameness. They are of limited usefulness in

the investigation of soft tissue injuries.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and

computed tomography (CT): Magnetic

resonance imaging is revolutionising the

field of equine diagnostic imaging and

orthopaedics. MRI scans use magnetic fields

to create images of the tissues inside the

body. MRI scans are increasingly common

in the investigation of lower limb and foot

conditions. CT scans use multiple X-rays to

create three-dimensional images of an area

and can provide high quality images of

both bone and soft tissue structures.

Figure 6

Radiograph of a horse suffering

from chronic laminitis

Figure 7

Ultrasound image of tendons in

a horse

Ultrasonography (‘ultrasound’) is the most

practical and accurate method for

assessing tendons (see Figure 7),

ligaments, and other soft tissues. Ultrasound

is an excellent way to view the soft tissue

structures in the horse. It allows real-time

imaging of the tendons and ligaments.

Figure 8

A bone scan of the pelvis being

performed in a horse

6

7

Scintigraphy (bone scan) is usually

performed in horses when the lameness

is very subtle, intermittent, or when a

non-displaced fracture (small crack) is

suspected. Bone scans are useful in horses

which are not amenable to nerve or

joint blocks.

During scintigraphy, the horse is given

an injection, which contains a small

quantity of radioactive material. The

radioactive material will become

distributed throughout the horse’s body

and can be detected using a gamma

camera, which is linked to a computer.

The information gained can be used to

determine sites of abnormality and thus,

possible causes of lameness. Scintigraphy

is safe for horses, but the horse must

remain at a special quarantine facility

for a short period following injection

of the radioactive material, usually for

24 - 48 hours.

The investigation of the lame horse involves

a structured and careful approach from

your vet which will ensure the highest

chance of finding the cause of the lameness.

The actual approach used by your vet may

utilise some, or a combination of these

techniques in order to discover the cause

of lameness.

IN SUMMARY

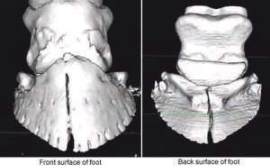

Figure 9

CT Scan: a 3-Dimensional image

of a fractured pedal bone